Michal Kruger: Nothing Fancy

We recently unveiled a new edition featuring Michal Kruger. Born in South Africa (1994) Kruger’s journey as an artist now finds him in the northern charm of Groningen. After earning his BA in Fine Art from Rhodes University in 2016, he went on to complete his MFA at the Frank Mohr Institute in 2020, bridging continents and sensibilities.

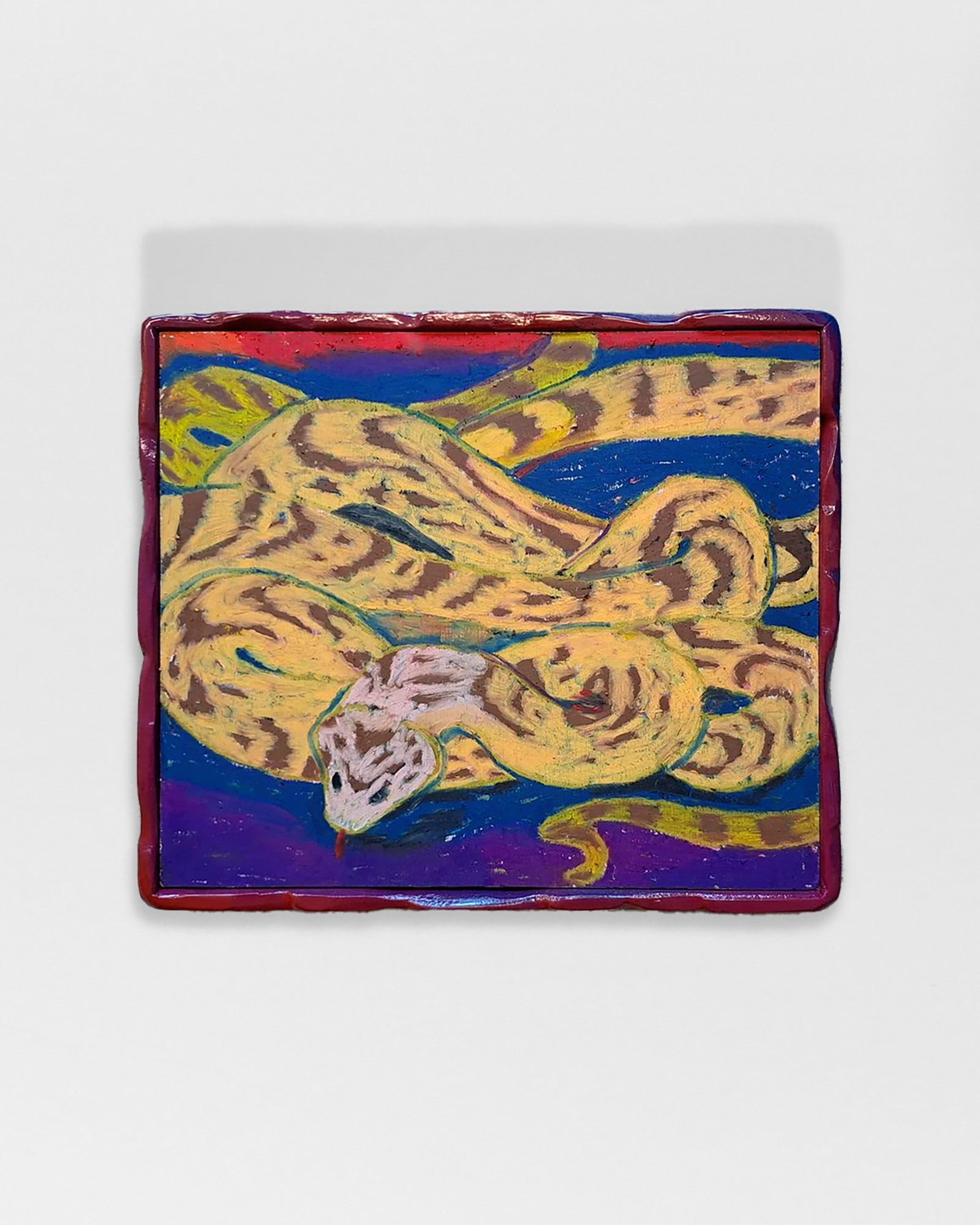

Michal’s works are a critical journey into the intersection of nostalgia and shame. Growing up in a post Apartheid era, he captures a collective and cultural white Afrikaner nostalgia for a place and time that never really existed.

MK: I painted and drew what I saw around me: a Dutch pastoral scene, cows, oranges, tractors, fields, lions, flags, animal skins, green grass, yellow grass, burnt grass, still lives, the big five, swimming pools, fences, pick-up trucks, dead cows, vultures, maps, buildings.

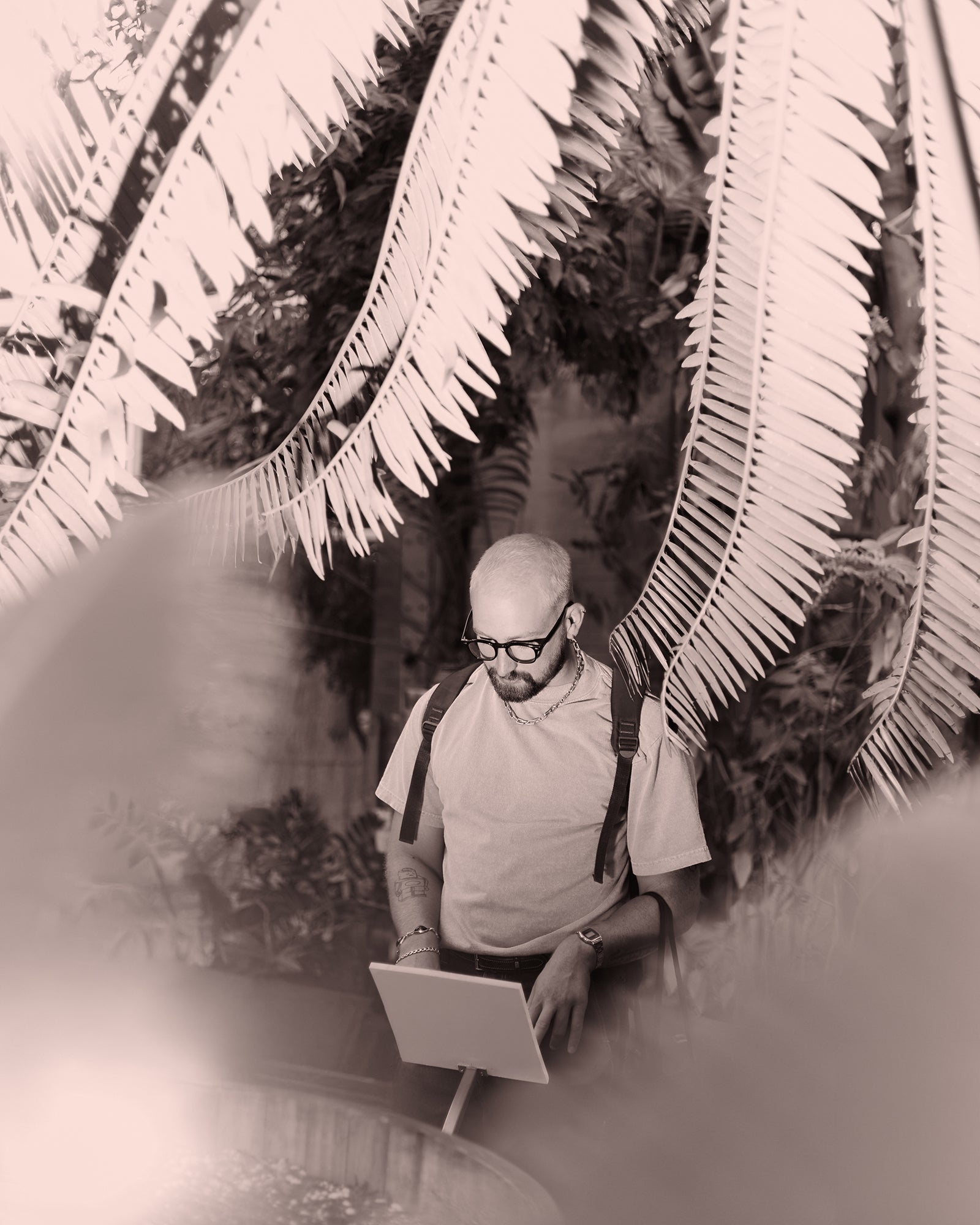

We meet Michal for a rainy-day walk through the Hortus Botanicus in Amsterdam, with hopes of visiting the South African section. Established in 1638, this corner of the garden is home to flora brought over by the Dutch East India Company. But on this day, instead of vibrant blossoms, we’re greeted by scaffolding — the section is in a sense ironically closed for renovations and is fenced off.

MK: I was born in 1994, the year Apartheid, the governing institution that separated white and black people in violent hierarchies, ended. The world had not changed for us and our families. The narrative proposed at home was that the black government was now in power and people should stop complaining about the past.

You often call yourself a full-time tourist. MK: “The contemporary white Afrikaner find themselves in a changing landscape and must seek to understand their place in it. Now I find myself thousands of kilometres away in the country of my ancestors. But I am caught by the confines of my preconceptions. Being white in South Africa is like being a tourist. You talk about your love of natural beauty and the unpopulated landscape. There is a barrier of privilege between you and the real world. A barrier of neatly planted agapanthus outside the fence. I must ask myself, what is it that I love about my country? Where do I find solace?”

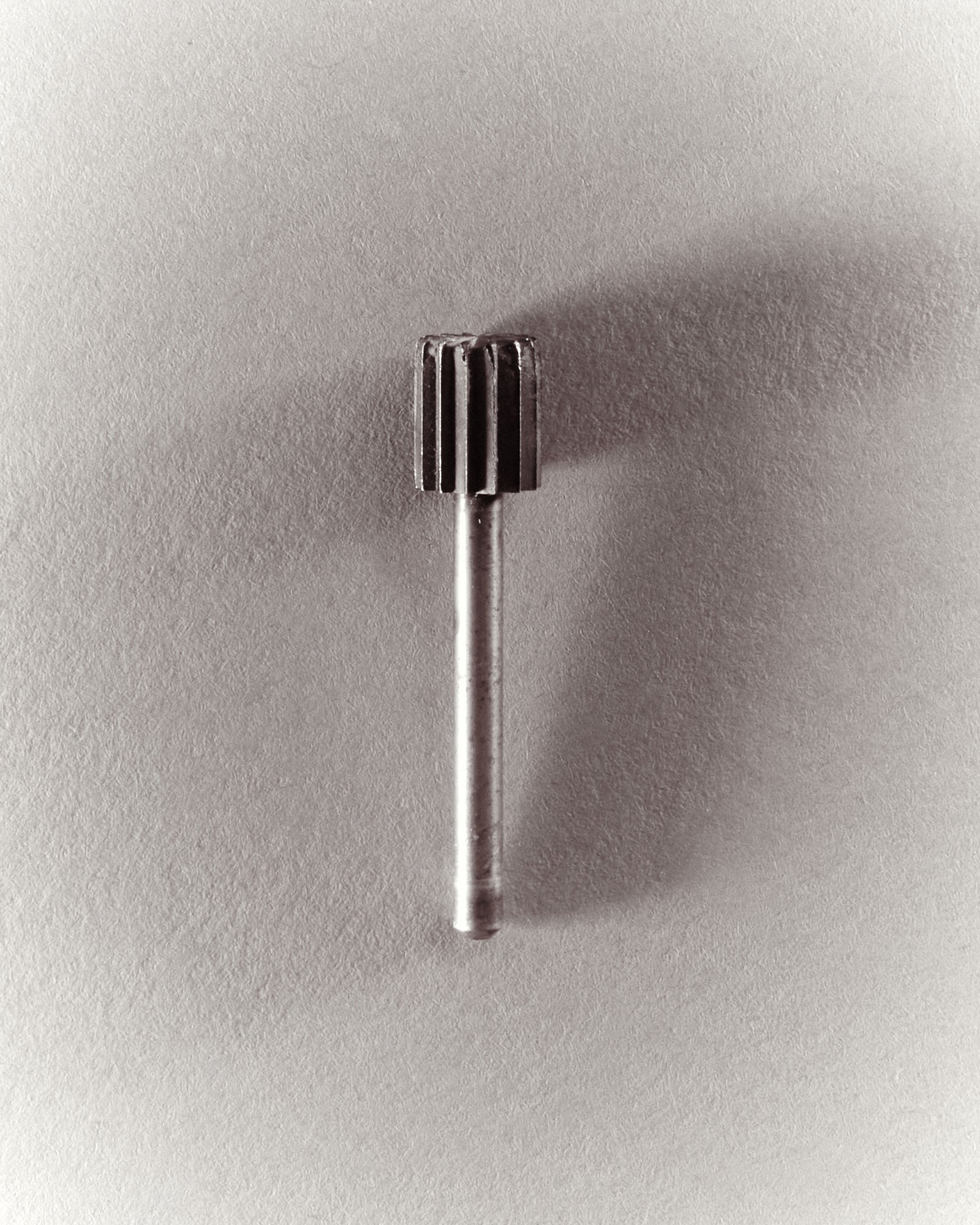

In your publication Wild Gardens, you mention several recurring motifs. Are there any keepsakes or mementos you hold onto that reflect your sense of being a visitor or a tourist? MK: There is this handmade wooden Landrover Defender, complete with a packed roof rack, as if it's going camping. It’s a souvenir that my parents bought when they were in Malawi, because their car looked exactly like this. The 4x4 drive appears often in your work. MK: We would go to dealerships and test drive smooth-smelling leather seats while my parents talked to some friendly man about things I didn’t understand. There is such a contrast between the maker of this object and the owners of such a car it represents.

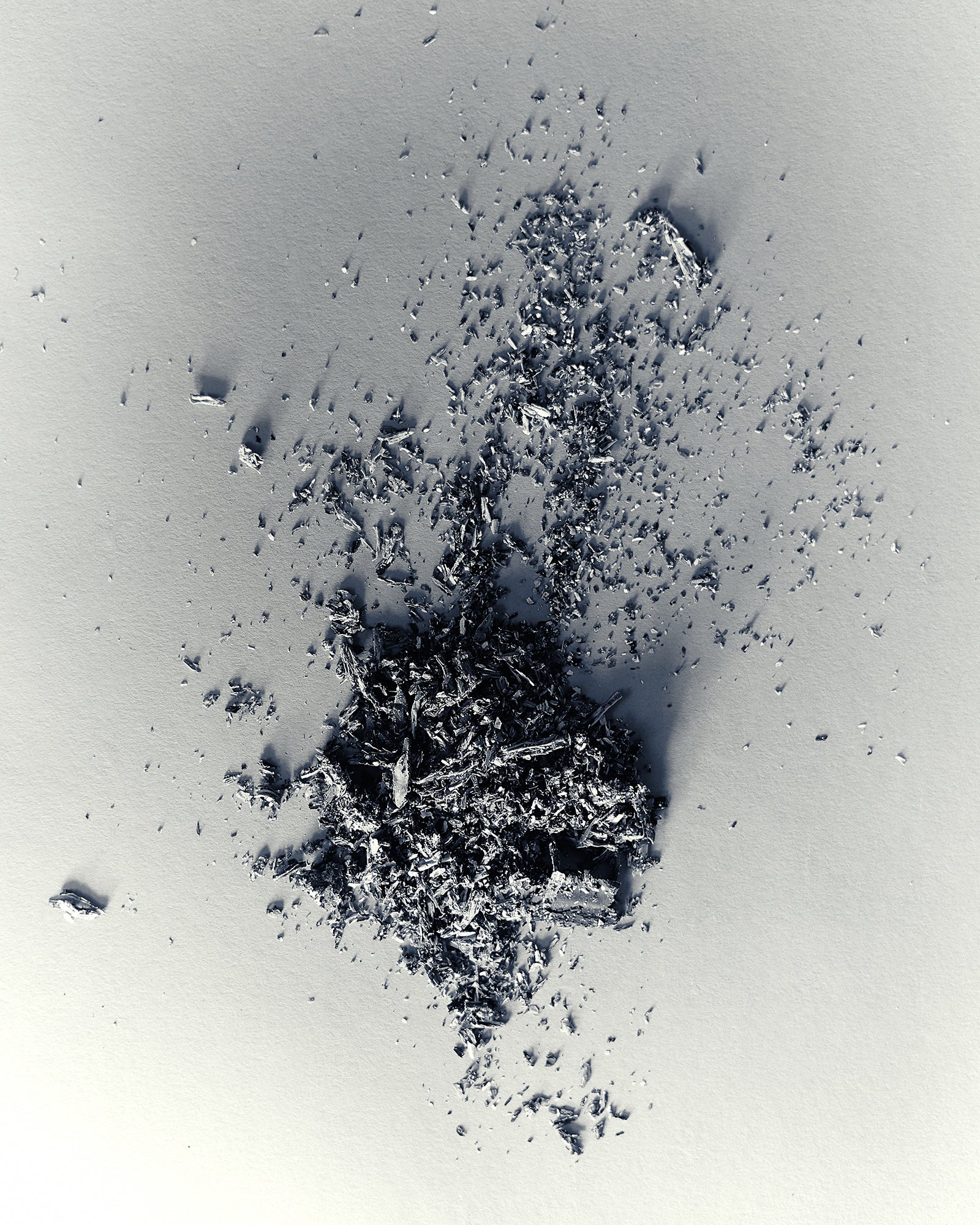

Michal pulls out a fries wrapper, something he’s kept for years — a humble yet curious reminder of a fleeting moment. MK: Actually, I never eat at Hungry Lion. The first time I went to one was when I got this packet. I was in South Africa with my boyfriend, and I took him there because I thought it would enhance the South African experience. I always used to go to a KFC in a much nicer part of town. I told my boyfriend we needed to go to Hungry Lion, just because it’s called Hungry Lion. And then I kept the wrapper — I guess to show that I’m the kind of person who eats there. Or as my mother would say; “Tonight’s supper is simple, nothing fancy.”

Text by Kees de Klein and Unfair. Images by Great Expectations