The Thomas Trum Machine

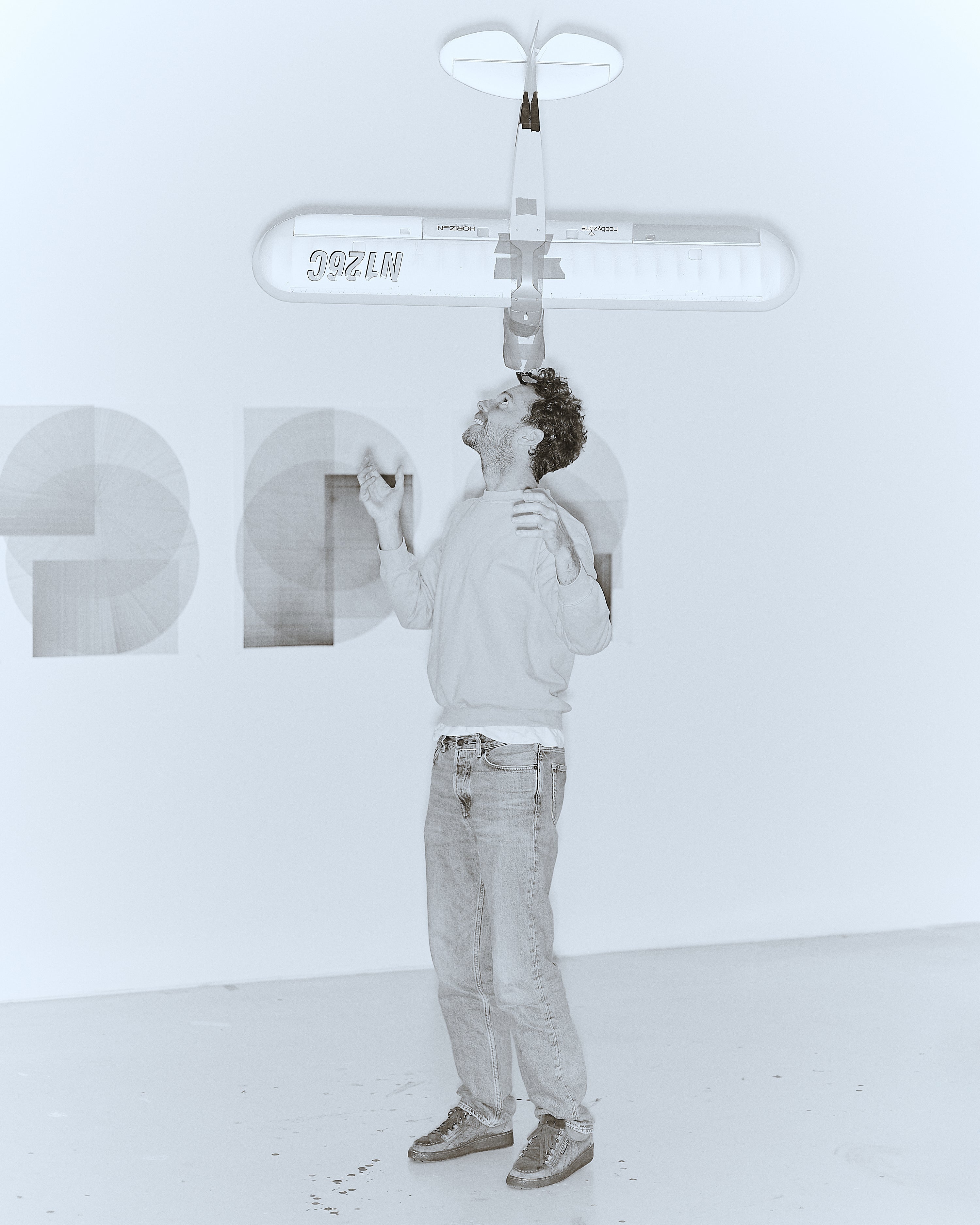

On a Monday morning, we find ourselves in a two-part studio on a large industrial complex in Den Bosch. We meet Thomas and his team in his smaller, 400m2 studio space, where the walls are painted a crisp white, almost like a white cube. In the center is a large table covered in one of Trum's signature patterns, where we sit down for a coffee and talk about his work and his latest edition, launching soon in collaboration with coffee brand Wakuli.

We've heard you started out as a house painter, is that right?

TT: Yeah. After art school, I had to start generating an income somehow. So people would ask, Hey, can you do this? In those early years, I went at it pretty hard. Like, you paint a house for a week, and that gives you financial freedom for three weeks to just be in your studio. You literally go around with your little coolbox and radio, and you're your own boss, which was fantastic. The big downside is that everything has to be white, or grey.

I have a huge passion for paint, for painting, and for the techniques that go with it. I’m deeply involved in that. Sometimes I'd go to a painting trade show, and that's amazing. They have the latest ladders, the newest rollers, the best brushes. It's super inspiring. I think craftsmanship is very important. In my work, too. I want the tool's signature to be left behind.

Are your tools also backwards compatible?

TT: If I went bankrupt tomorrow, I could just start a painting business. I’ve got everything—lifts, ladders, spray equipment, all pretty advanced stuff. I always joke about that. I even have one of those contractor vans.

If I went bankrupt tomorrow, I could just start a painting business.

So in a way, you're still working within the same system as back then, for most of the time.

TT: Yeah, and it's great because I know so much about it. It’s also super cool to apply that technical knowledge. I'm always looking for ways to do that because it leads to new discoveries, new uses... Well, new applications, really. I painted a swimming pool in France. It’s a concrete basin permanently filled with seawater. Technically, that’s a huge challenge. No one wanted to advise me on it. They’d say, Yeah, I get it, but I can't really give you advice. They didn’t dare. They said it would never work. Eventually, I found a company, through some connections, that specializes in offshore coatings. Really intense business.

Is it the artist mastering the material, or the material mastering the art?

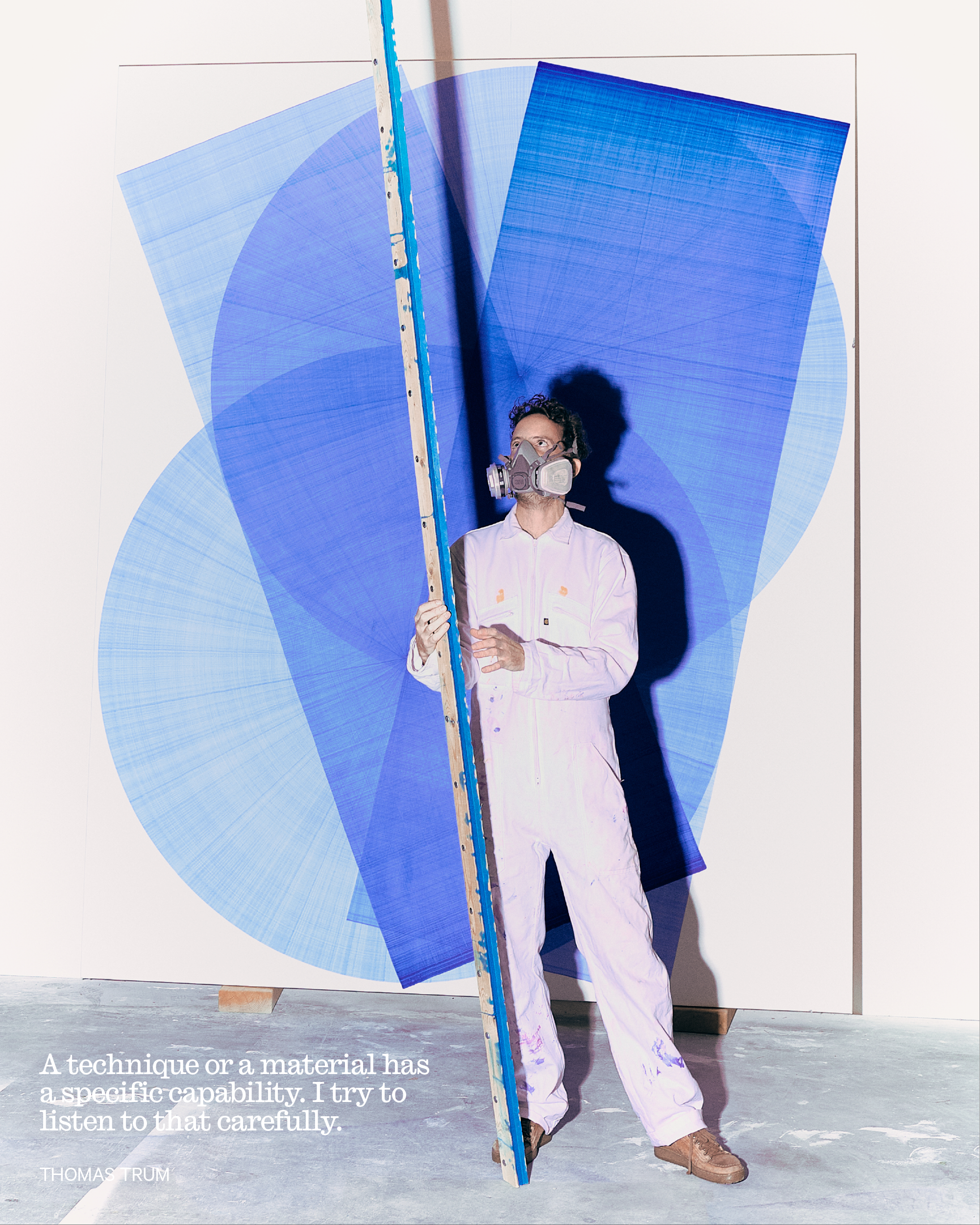

TT: Yeah, I think it’s very much hand in hand. Often, a technique or a material has a specific capability. I try to listen to that carefully and find a way to make it visible in a new way.

A technique or a material has a specific capability. I try to listen to that carefully.

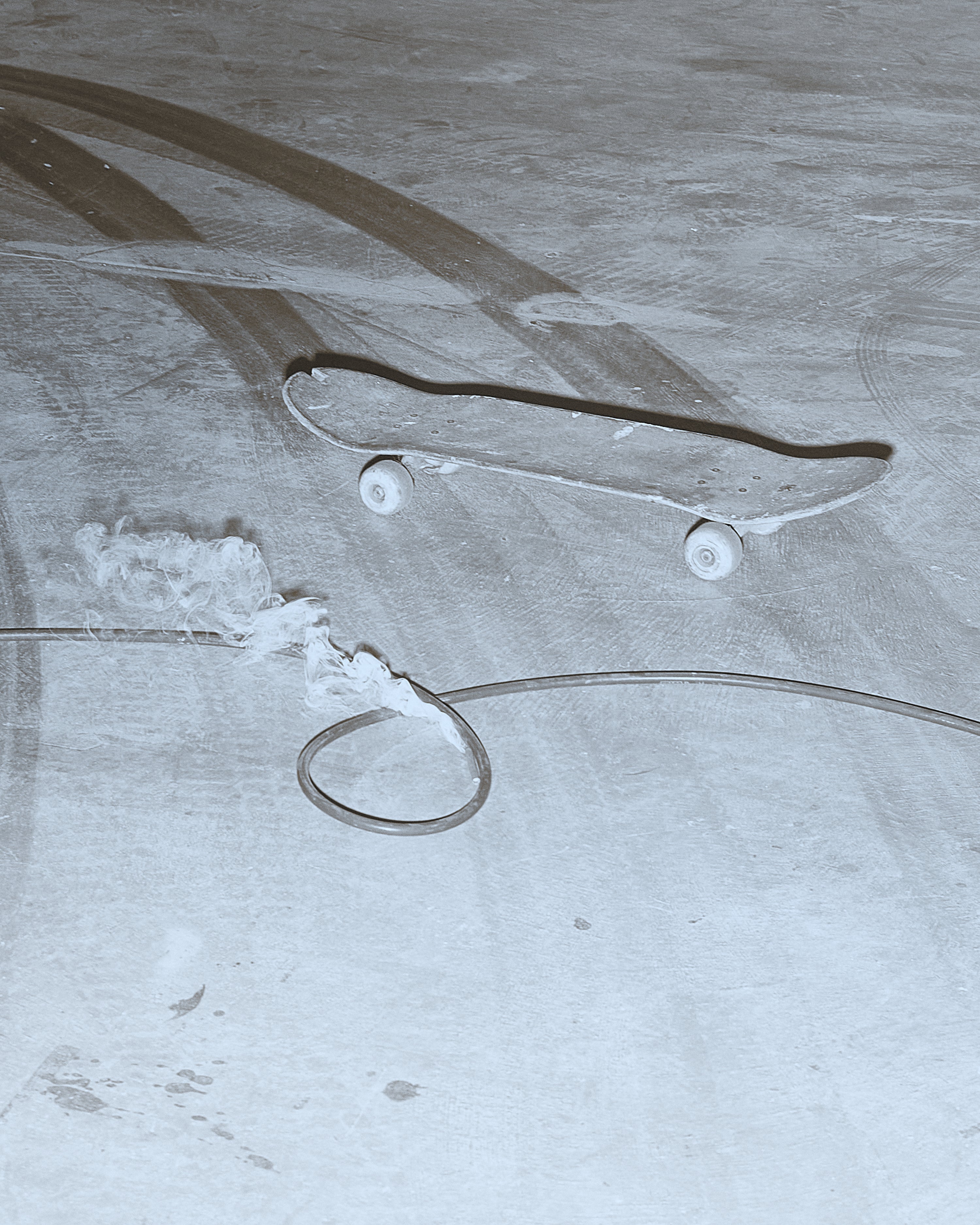

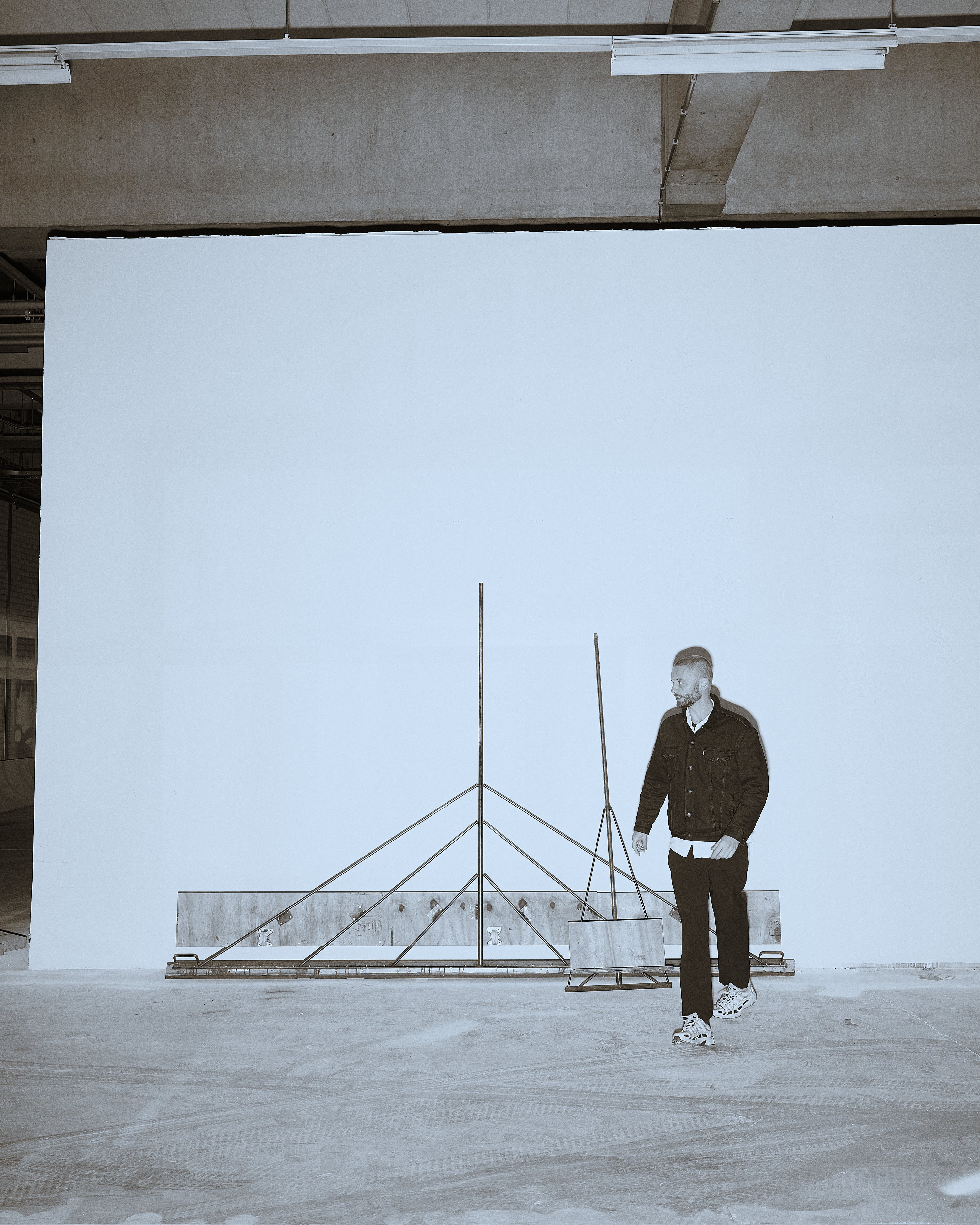

We walk around the complex to visit studio 2, a massive 5000m2 industrial hall. Different tools and workstations are spread round the space, like a golf cart, scissor lift, paint spraying machines and giant handmade “markers” that Trum uses to make his largest works.

Would you rather drive a lift than a Lambo?

TT: Yeah, a lift for sure. My dream project would be to work with Michelin to make tires that aren’t necessarily about the best grip, but that leave an exciting track or something like that. And then put them on a Porsche. That would be really exciting.

And if, say, Sharpie calls you and says, We want to make a marker that’s one meter long, and everyone starts making mini-Thomas Trum pieces, how would you feel?

TT: I wouldn’t be opposed to it. We're kind of in a Warhol phase. I’ve started having Aukje and Mieke make some of my drawings. At first, they said, You can’t do that, you really can’t. But after a bit of training, you can’t see the differences anymore.

Right now, we’re messing around with model planes. We’re diving into film, photography, and technically operating these machines. It's about finding materials that can stay suspended in the air. We’ve been working on that for almost a year now. It takes so much thought—you have to reinvent everything.

You know that old documentary, Style Wars, about the beginnings of graffiti? There's a scene where three guys are discussing, Oh, I found my mom’s cleaning spray. If you put that cap on this, you get a line like this, and with another cap, you get a line like that. They were pioneering how to create the best lines. Now you can go to the store and buy everything ready-made.

The great equalizer between everything is the balance between optimization, reproducibility, and human action.

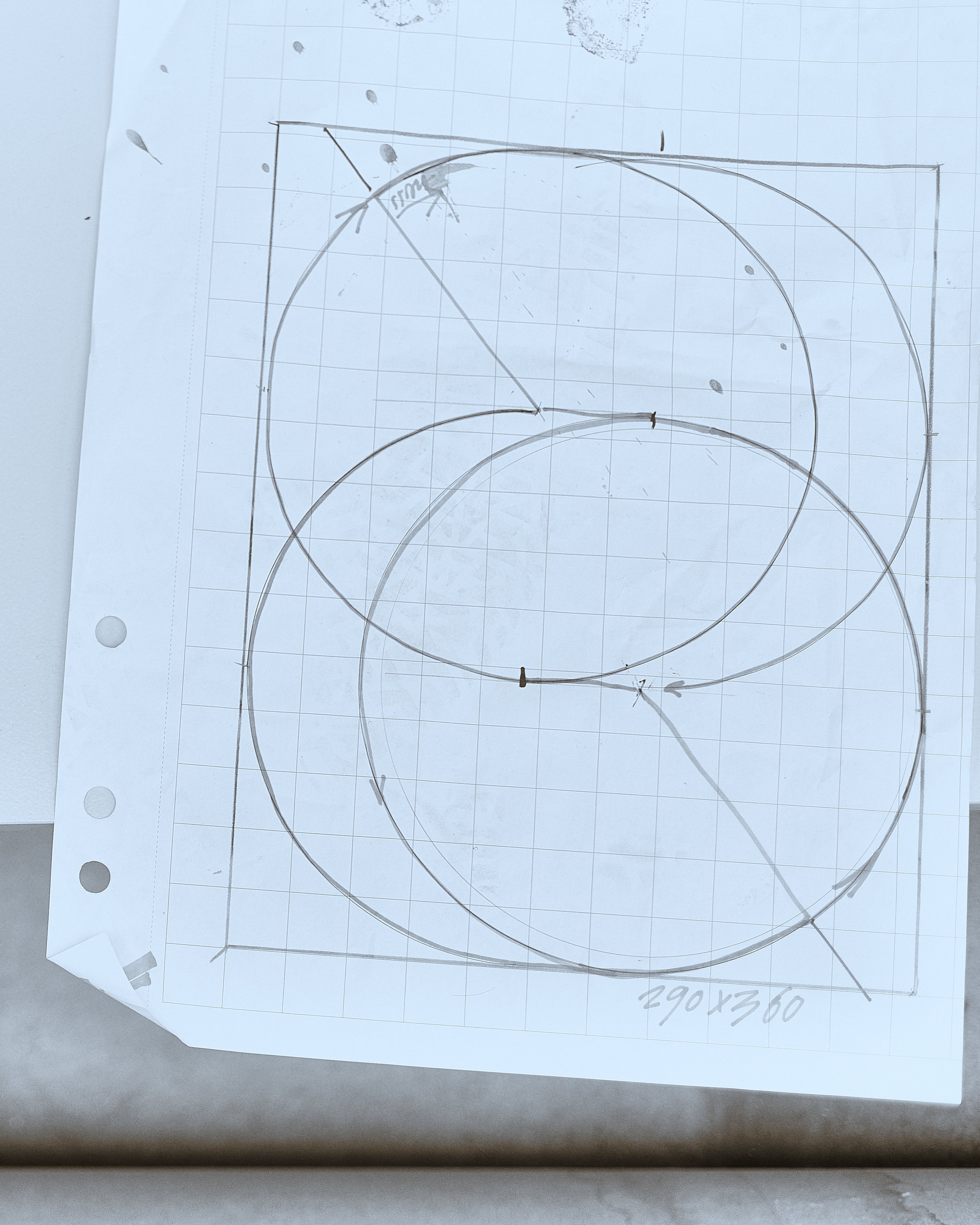

This Sunday, I was flying over this. Thomas shows an image of an agricultural landscape snapped from the plane window. I just sat and stared out the window all night. The extreme efficiency in agriculture, it’s all about working with surfaces, lines and optimization. It’s so cool. It’s basically a one-to-one match with my work.

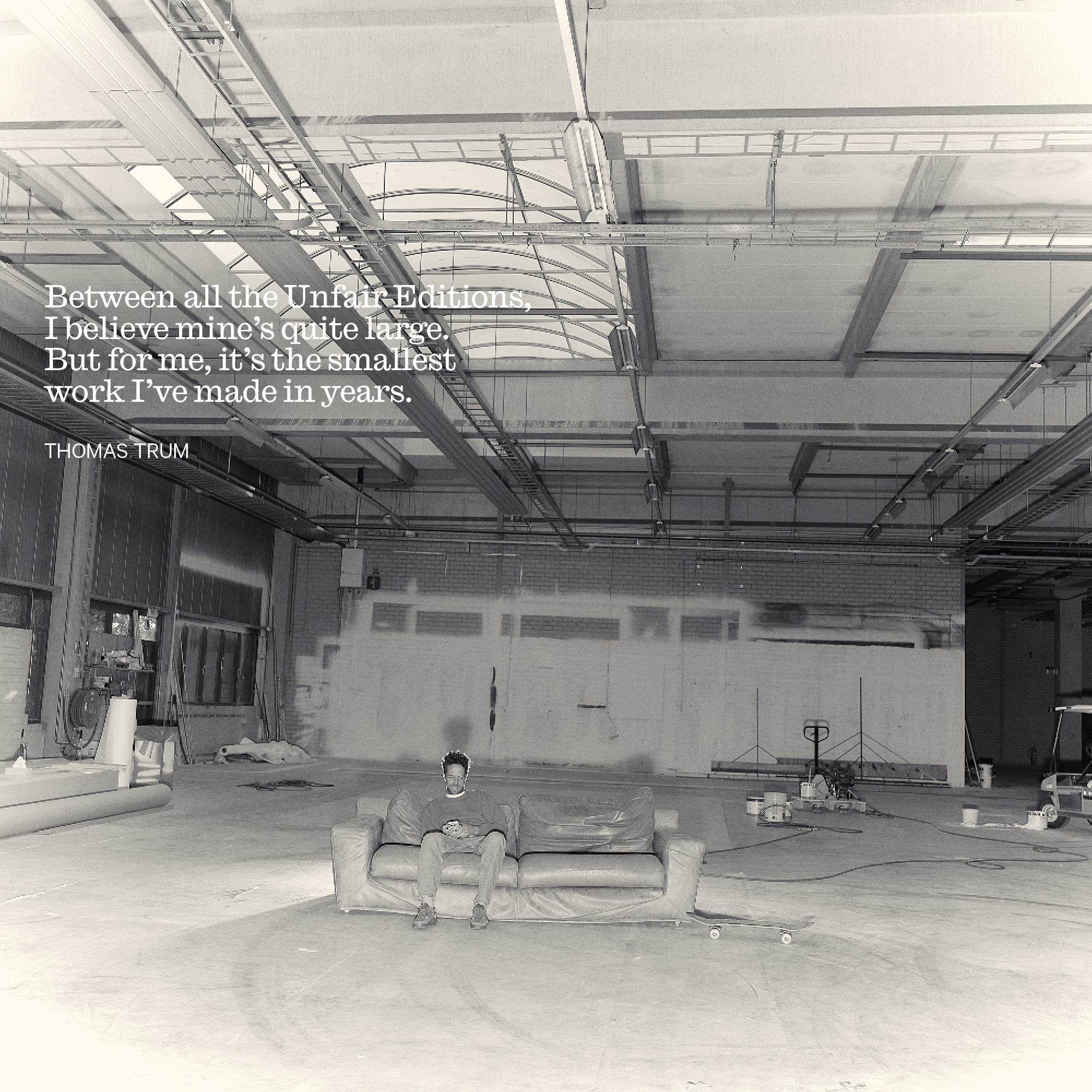

TT: I mostly work in large spaces, sometimes even with up to five people making one line at the same time. Between all the Unfair Editions, I believe mine’s quite large. But for me, it’s the smallest work I’ve made in years. But if you put it in a house, it’s actually quite large again. It’s not a digital, reproduced print. I just repeated the same physical process for 75 times. And I’d say... that makes it much more interesting for me. The great equalizer between everything is the balance between optimization, reproducibility, and human action. If you look at my work without any reference to scale, and you put small next to large, you can’t really tell the difference. And I think that’s super cool. It draws you in.

So the ultimate Thomas Trum machine is just made up of people?

TT: Pretty much, yeah. It takes a team to make a Trum.

Text by Kees de Klein and Unfair. Images by Great Expectations